What Is The Most Important Tool For Interest Groups Seeking To Change Or Influence Public Policy?

Executive Summary

How often and in what circumstances practice interest groups influence US national policy outcomes? In this article, I innovate a new method of assessing influence based on the judgments of policy historians. I amass information from 268 sources that review the history of domestic policy making across xiv domestic policy issue areas from 1945 to 2004. Policy historians collectively credit factors related to involvement groups in 385 of the 790 pregnant policy enactments that they identify. This reported influence occurs in all branches of government, merely varies across time and policy expanse. The almost commonly credited form of influence is general support and lobbying past advocacy organizations. I also take advantage of the historians' reports to construct a network of 299 specific interest groups credited with policy enactments. The interest group influence network is centralized, with some ideological polarization. The results demonstrate that interest group influence may be widespread, even though the typical tools that we utilise to appraise it are unlikely to observe it.

Public policy is the ultimate output of a political system and influencing policy is the primary intent of interest groups. Yet involvement group scholars have had difficulty consistently demonstrating interest group influence on policy. As a result, we are left with incomplete answers to some basic and important questions: How often exercise involvement groups influence policy change? In what venues and what policy areas is interest group influence most common? Is involvement group influence increasing or decreasing? Do certain types of organizations or tactics influence policy more than others?

This commodity addresses all of these questions by relying on the judgments of historians of American domestic policy. It reviews the perceived influence of interest groups on pregnant policy changes enacted by the American federal government since 1945 in 14 policy areas, enabling an assessment of the frequency of interest group influence as well as variation across venues, upshot areas, groups, tactics, and fourth dimension periods. Footnote i Rather than offer definitive answers, this offers a new type of appraisal of interest group influence. It aggregates the explanations for pregnant policy enactments found in qualitative histories of individual outcome areas such as environmental policy and transportation policy. Footnote 2 The authors of these histories typically do not fix out to assess interest group influence. They intend to produce narrative accounts of policy development. In the process, they identify the actors most responsible for policy change and the political circumstances that fabricated policy change likely, including just not express to interest group activeness. Assembling their explanations offers a new perspective on the role of interest groups in policy change.

I use 268 historical accounts of the policy making process, each covering 10 years or longer of mail service-1945 policy history, as the raw materials for the analysis. Footnote 3 Past using secondary sources, I can aggregate information about 790 U.s.a. federal policy enactments that were considered significant by policy historians, including laws passed past Congress, executive orders by the President, administrative agency rules and federal courtroom decisions. Footnote 4 Policy historians do not assume that every involvement group can be effective or that every group is influential for the aforementioned reasons. Their enquiry enables a await at differences in policy influence across groups and contexts. They assess the function of interest groups as one piece in a multifaceted policy making organization.

In what follows, I track when, where and how interest groups influenced policy change, co-ordinate to policy historians. First, I review the findings and the research strategies pursued in scholarship on interest group influence and abet the utilise of policy histories. Second, I describe my method of aggregating explanations for policy change from policy histories. Tertiary, I review the factors related to interest groups and the types of groups that are credited in explanations for policy change. Fourth, I investigate variation in interest groups influence beyond time and issue areas. Fifth, I construct and analyze a network of specific interest groups credited with policy enactments, including its structure and the particular interest groups that are central. Sixth, I review the limitations of using the commonage judgments of policy historians to assess interest grouping influence. I conclude with an evaluation of scholars' current strategies for assessing influence, arguing that current research might not uncover the kinds of influence noted past policy historians.

Research on Involvement Group Influence

Studies of the policy process signal that interest groups often play a central office in setting the government agenda, defining options, influencing decisions and directing implementation (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993; Berry, 1999; Patashnik, 2003). In their meta-analysis of studies of influence, Burstein and Linton (2002) bear witness that interest groups are often establish to accept a substantial affect on policy outcomes. Yet most studies of influence await at particular issue areas and organizations, rather than generalize across a big range of cases (Baumgartner and Leech, 1998).

Studies of influence that do attempt to generalize suffer from the inherent difficulty of measuring influence. 1 type of study uses surveys or interviews with interest group leaders or lobbyists, mostly relying on cocky-reports of success (Holyoke, 2003; Heaney 2004). This tells us only what group tactics are associated with success as perceived by each group. A second blazon of written report selects a measure of the extent of interest grouping activity, peculiarly Political Action Committee (PAC) contributions or lobbying expenditures, and associates it with legislative outcomes. The big literature on the part of PAC contributions on gyre phone call votes found no consequent effects on votes (Wawro, 2001), but there is some prove that contributions may heighten the level of involvement in legislation already supported by the legislator (Hall and Wayman, 1990). A third type of report changes the dependent variable from policy influence to lobbying success. This allows scholars to assess who is on the winning side of policy debates based on interest group coalition characteristics (Baumgartner et al, 2009; Mahoney, 2008). Withal these assessments do not incorporate the many other factors unrelated to interest groups that predict the success and failure of policy initiatives.

Inquiry that has generated consequent bear witness of influence is rare and tends to focus on narrow policy goals rather than significant policy enactments. Activity past groups with non-ideological or uncontroversial causes, for instance, may accept some effect (Witko, 2006). Business is well-nigh effective when it has little public or interest grouping opposition (Smith, 2000). Resources spent directly to procure earmarks tin can be effective (de Figueiredo and Silverman, 2006). Full general studies of interest group influence have been able to definitively demonstrate only conditional and small furnishings, ofttimes on modest policy outcomes. Even studies of lobbying success, rather than influence, tend to demonstrate the potential to stop policy change rather than to bring information technology about (Baumgartner et al, 2009). Despite the many instance studies that find prove of interest group influence on major laws (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993), administrative actions (Patashnik, 2003) and court decisions (Melnick, 1994), aggregate studies of influence based on the resources spent past each side neglect to demonstrate that interest grouping activity tin lead to major policy enactments.

Scholars have likewise sought to use network analysis to understand how interest group relationships might lead to policy influence. Heinz et al (1993), for example, find that well-nigh policy conflicts feature a 'hollow core', with no one serving as a central player, arbitrating conflict. Grossmann and Dominguez (2009), in dissimilarity, notice a core-periphery structure to involvement group coalitions, with some advocacy groups, unions and business height associations playing central roles. Notwithstanding most network analyses are based on endorsement lists or reported working relationships, rather than influence. Footnote 5 At that place has been no endeavor to look at a big number of meaning policy enactments over a long historical menses and appraise the design of interest group influence.

The Perspective of Policy History

In contrast to scholarship on interest groups, policy histories do non involve a search for prove that interest groups are influential. Interest groups only enter the explanation to the extent that a policy historian telling the narrative of how and why a policy change came about is convinced that the role of involvement groups was of import. These authors rely on their ain qualitative research strategies to identify significant actors and circumstances. The 268 sources used here quote get-go-hand interviews, media reports, reviews past government agencies and secondary sources. The authors of these books and articles were issue area specialists, primarily scholars at universities, but also including some journalists, recall tank analysts and policymakers. Footnote half-dozen They select their explanatory variables based on the plausibly relevant circumstances surrounding each policy enactment with attention to the factors that seemed dissimilar in successes than failures, though they rarely systematize their pick of causal factors across cases. I rely on the judgments of these experts in each policy area, who take already searched the most relevant available show, rather than impose one standard of evidence across all cases and independently comport my own analysis.

One benefit of such an approach is that policy historians do not come to the inquiry with the baggage of interest group theory or intellectual history. For instance, they do not necessarily presume that interest groups take difficulty overcoming collective activity bug or that resources are the main reward of some interests over others. Another benefit is that they expect over a long fourth dimension horizon, rather than a single congress or presidential administration. This allows them to consider how policy adult and to review many original inside documents from policymakers. Policy historians cannot be said to produce the just reasonable account of involvement group influence, simply they collectively offer a different kind of evidence based on an independent fix of investigations that can be productively compared with the findings from interest group research.

The literature that I compile does non share a single theoretical perspective on the policy process. The authors see themselves as scholars of the idiosyncratic features of each policy surface area, besides as observers of case studies of the general features of policy making. To the extent that policy history offers a unique theoretical perspective on interest group influence, it points to the interdependence of interest groups with their political context and the vastly diff capacity for influence among groups. Scholars of interest groups are sensitive to the political context that groups face, but they would be less likely to consider whether involvement groups lack influence in certain fourth dimension periods or issue areas considering other actors predominate. Policy historians are merely as probable to betoken to a powerful administrative agency leader or long-serving member of Congress as to assign credit to interest groups. Scholars of interest groups also look at differences in access or capacity beyond groups, but they rarely consider the possibility that only a few large, well-known groups have what it takes to help alter policy outcomes. Merely as policy historians ignore well-nigh members of Congress in their retelling of the events surrounding policy development, well-nigh interest groups and lobbyists never do enough to leave their imprint on policy history.

Aggregating Policy Expanse Histories

To appraise involvement group influence on policy enactments, I use in-depth narrative accounts of policy development. Policy historians catalog the important output of the policy making procedure and attempt to explain how, when and why public policy changes. David Mayhew (2005) uses policy histories to construct his list of landmark laws; he defends the histories as more witting of the effects of public policy and less swept up by hype from political leaders than contemporary judgments (Mayhew, 2005, pp. 245–252). Since Mayhew completed his review in 1990, there has been an explosion of scholarly output on policy area history. Yet scholars take not systematically returned to this vast trove of information. My analysis expands Mayhew'southward (2005) source listing by more than 200 per cent.

In what follows, I compile information from 268 books and articles that review at least one decade of policy history since 1945. Footnote 7 The sources cover the history of 1 of 14 domestic policy issue areas from 1945 to 2004: agriculture, civil rights & liberties, criminal justice, instruction, energy, the environment, finance & commerce, health, housing & customs development, labor & immigration, scientific discipline & technology, social welfare, macroeconomics, and transportation. Footnote viii This excludes defense, trade and foreign diplomacy, but covers the entire domestic policy spectrum. Footnote nine I obtained a larger number of resources for some areas than others only analyzing boosted volumes covering the aforementioned policy area reached a bespeak of diminishing returns. In the policy areas where I located a large number of resources, the first v resources covered most of the pregnant policy enactments. The full list of sources, categorized by policy area, is available on my web site. Footnote 10

The next step was reading each text and identifying pregnant policy enactments. I primarily used 10 research administration, grooming them to identify policy changes. Other assistants coded individual books. I followed Mayhew'south (2005) protocols but tracked enacted presidential directives, authoritative agency actions and courtroom rulings along with legislation identified by each author as significant. I include policy enactments when any writer indicated that the alter was of import and attempted to explicate how or why it occurred. Equally a reliability check, pairs of assistants assessed the same books and identified 95 per cent of the aforementioned significant enactments. For each enactment, I coded whether it was an act of Congress, the President, an administrative agency or department, or a court.

I coded any mentions of factors related to involvement groups that may influence policy modify. Coders asked themselves 61 questions about each author's caption of each change from a codebook. Thirteen of these questions involved interest groups. For example, I coded whether authors referred to Congressional lobbying, protestation or grouping mobilization, fifty-fifty without naming specific groups. Some authors as well referred to categories of involvement groups (such as an industry or 'environmentalists') without mentioning specific organizations. I tracked all of these references to interest groups in author explanations for policy enactments. Interest groups include corporations, trade associations, advocacy groups or any other private sector organizations. I record 13 dichotomous indicators of the blazon of interest group influence and the type of interest grouping cited.

This produces a database of where involvement grouping factors were credited by each writer. Coders of the same volume reached understanding on more than 95 per cent of all codes. Footnote xi Comparisons of different author explanations for the same enactment showed that some authors recorded more explanatory factors than others. In the results below, I aggregate explanations across all authors, considering involvement group factors relevant when any source considered them part of the reason for an enactment. I review potential biases in policy histories and potential bug with my aggregation methods in the limitations section of the commodity.

A similar method was successfully used by Eric Schickler (2001) to assess theories of changes in Congressional rules. The method is also related to the analysis performed by John Kingdon (2003), but his assay relies on his own first-hand interviews, whereas this article compiles the first-hand enquiry of many unlike authors. Like meta-analysis, the method aggregates findings from an array of sources to wait for patterns of findings. In this respect, it is similar to Burstein and Linton's (2002) study of 53 periodical articles. Every bit the original works in this case are case studies or historical narratives, however, the results are descriptive and exercise not presume uniformity of method.

Several robustness checks confirmed that using qualitative accounts of policy history produces reliable indicators. Starting time, different authors produce similar lists of relevant coexisting factors in each enactment. Second, authors covering policy enactments exterior of their area of focus (such as health policy historians explaining the political process behind general tax laws) also reach near of the same conclusions about what circumstances were relevant equally specialist historians. 3rd, there were few consistent differences based on whether authors used interviews, quantitative data or archival research; whether the authors came from political scientific discipline, policy, police, sociology, economics, history or other departments; or how long after the events took place the sources were written.

Reported Interest Grouping Influence on Policy Change

According to policy historians, interest groups are involved in pregnant policy enactments quite ofttimes. Interest groups were partially credited with 279 pregnant new laws passed by Congress (54.viii per cent of all significant legislative enactments), 31 meaning executive orders (41.3 per cent of the total), 35 significant administrative agency rules (39.3 per cent of the total) and 46 significant judicial decisions (36.8 per cent of the total). Policy historians thus credit interest group factors with playing a role in policy making in every type of federal policy making venue, but most ofttimes in Congress. Interest group activities are sometimes mentioned as the sole explanatory factor in these explanations; more normally, they are mentioned in combination with other factors such every bit focusing events, media coverage, negotiations among authorities officials and the support of specific policymakers.

Even though there are of import differences in explanatory factors for policy enactments in unlike branches of authorities, interest groups are commonly credited actors in all three branches. In one instance, Studlar (2002) describes a case of brinksmanship between authoritative agencies and regulated corporate interests over the circulate ban on tobacco advertising. In another context, Studlar (2002) reports, the administration partnered with involvement groups in the legislature by acting to classify tobacco equally a carcinogen: '2d hand smoke became a major issue after the Surgeon General'south written report of 1986. In an endeavor to help classify this attribute of tobacco and to get the ball rolling with interest groups and the promotion of legislation, the EPA took command'. Interest groups are besides credited with actions past the President, such as Bill Clinton'southward guidelines on religious expression in schools (Fraser, 1999, p. 205). Interest groups are credited with policy changes in the courts equally well, even though courts are the venue where the average interest group is less involved (Schlozman and Tierney, 1986). Well-nigh interest groups credited with courtroom rulings brought the relevant example to the courts, though some only authored influential amimus briefs.

Table 1 reports the specific types of involvement grouping factors mentioned in explanations for policy change. General interest group support was mentioned in conjunction with 22 per cent of policy enactments (this was a residual category, when no specific tactics were referenced). Most oft, a specific organization was referenced for developing a proposal or for their work on behalf of policymakers. On other occasions, a wide coalition was involved in promoting policy alter.

Congressional lobbying was mentioned every bit an of import factor in sixteen per cent of significant policy enactments. According to Davies (2007), for case, the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) came about as a result of lobbying after an important foreign policy consequence: 'It was Sputnik that led the consequence to catch fire …. In the case of NDEA, lobbyists … seized their opportunity and swarmed over the Hill'. Other explanations, such as ane for the National Mental Health Act, relied on particular lobbyists: 'The bill had friends in Congress, … in the affected agency, among interest groups, and in the press …. The new element which seemed to fill the gap … was a full-time, unmarried-minded, paid lobbyist' (Strickland, 1972, p. 46).

Constituent mobilization was mentioned in a meaning minority of cases but was not as commonly credited as direct lobbying. One example was the campaign for the Social Security Disability Reform Act: 'The legislation was a response to thousands of individuals who had requested an entreatment of their termination of benefits. Advocacy organizations … contacted members of Congress with horror stories about individuals who waited more than a twelvemonth for review of their entreatment' (Switzer, 2003, pp. 54–55). Other involvement groups gained a status every bit representing an important constituency; this translated into legislator support. Mitchell (1985), for example, reports that the Veterans' Abode Loan Benefit passed to gratify a key constituency: 'Veterans … this politically powerful group had strong claims on the nation's gratitude and conscience; objections to special treatment for veterans were easily fabricated to announced churlish and fifty-fifty unpatriotic'.

The research role of interest groups reportedly made a difference in policy outcomes as well. Reports by not-governmental organizations were associated with over ix per cent of pregnant enactments. Yet not all factors related to interest groups were judged commonly influential. Resources advantages on one side of an issue, new grouping mobilization, protests and a group switching sides in a policy contend were each mentioned infrequently.

When specific types of involvement groups are mentioned, advocacy groups are credited virtually often. Table 2 reports the types of interest groups that are referenced most oft in explanations for policy change. The 'advocacy groups' category includes public involvement groups, single-event advocates and representatives of identity groups. The 'business interests' category includes individual businesses, trade associations and peak associations. Advocacy organizations are mentioned far more often in explanations for postal service-war policy change than unions, professional associations or business interests. In fact, advocacy organizations are reportedly associated with 33.8 per cent of all pregnant policy enactments. Business interests were as well partially credited with 19.viii per cent of enactments. This is consistent with Berry's (1999) finding that denizen groups had a stronger influence on the government agenda than business interests. It besides reflects the fact that business organisation groups are unduly probable to lobby confronting policy changes rather than support them (Baumgartner et al, 2009). Academics, including scientists, are also reportedly influential in some cases (10.half-dozen per cent of the time). In that location is less frequent reported interest past unions, professional associations and call back tanks. When mentioned, many of these other types of involvement groups are credited in conjunction with an advocacy organization. The strong relative influence of advocacy organizations is hit, given that business and professional interests outnumber them by a big margin (Walker, 1991), but it reflects their unique advantages in reputation and perceived public back up (Berry, 1999; Baumgartner et al, 2009; Grossmann, 2012).

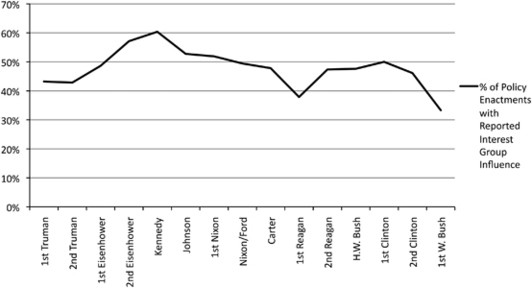

Reported involvement group influence has varied over time. Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of explanations for policy change involving interest groups since 1945 past presidential administration. The results indicate that reported interest group influence rose from the 1940s to the early on 1960s then declined to under 50 per cent. There followed two clear drops in reported group influence: during the 1st Ronald Reagan Administration and the 1st George W. Bush Administration. This does non necessarily indicate that interest groups had less influence on these item presidents, every bit most of the enactments took place in Congress; the administrations are given only as indicators of the fourth dimension periods. Overall, the frequency of interest grouping influence remained in a narrow range betwixt simply under 40 per cent and but over sixty per cent of enactments during the unabridged postal service-war period. For interest group research, the nigh hitting finding is that reported interest group influence failed to increase during the numerical explosion of group mobilization and advocacy in the 1970s (Berry, 1989). Perhaps more organizations brought more competition to influence policy without increasing the overall clout of interest groups in the policy making procedure.

Policy enactments with reported involvement grouping influence across fourth dimension.The graph records the per centum policy enactments reportedly involving interest groups during each quadrennial administration. The administration names are illustrative of the time periods and exercise not imply influence on presidents.

Interest group influence is reportedly more common in some policy areas than others. Tabular array 3 reports the per centum of policy changes involving interest groups by major domestic policy domain. Interest groups were most frequently involved in policy changes in the environment and civil rights & liberties, where they were partially credited with more than two-thirds of policy changes. This is unsurprising given the large related advocacy communities. Interest groups like the American Farm Agency and the Farmers Matrimony were usually credited with agriculture policy changes. Transportation policy is more than frequently associated with corporate influence than other sectors. Factors related to groups were also credited in at to the lowest degree half of policy enactments in housing & development, labor & immigration, and macroeconomics. Groups were least commonly credited with policy modify in criminal justice, merely they reportedly played a role in at least 30 per cent of significant enactments in all areas. Reported group influence varies widely across issue areas only is never absent. Advocacy organizations were the most oftentimes credited type of interest grouping in most upshot areas, although corporations and their associations were more common in energy, finance, macroeconomics, science and transportation. These event areas feature substantial government financing and business regulation, but take non stimulated equally many prominent advocacy groups.

Involvement Grouping Influence Networks

To investigate the roles that detail interest groups play in policy enactments and the relationships amongst these groups, I use social network analysis. I compile lists of interest groups involved in policy enactments from the 268 policy histories. For each policy enactment mentioned past each author, I catalog all mentions of credited groups. I then combine explanations for the aforementioned policy enactments, aggregating the groups that were associated with policy enactments across all authors. The result is a database of which interest groups were judged of import for, or partially credited with, each policy enactment. Coders of the same volume reached agreement on more than than 95 per cent of actors mentioned as responsible for each enactment. Footnote 12 I likewise categorized the actors ideologically, based on whether they were liberal (seeking to expand the telescopic of regime responsibleness) or conservative (seeking to contract the telescopic of government responsibility), or neither. All of these assessments were highly consistent across coders; actors that could not be hands categorized were put in a separate unidentified category.

Combined, the policy histories identify 299 specific involvement groups that they partially credit with at least ane policy enactment. I use an amalgamation network to understand their relationships. The network is based on the participants that were jointly credited with each policy enactment. The network ties are undirected but they are valued as integer counts of the number of shared policy enactments between every pair of interest groups. Footnote xiii This does not necessarily signal that the actors actively worked together, only that they were both on the winning side of a significant policy enactment and that a policy historian thought they each deserved some credit.

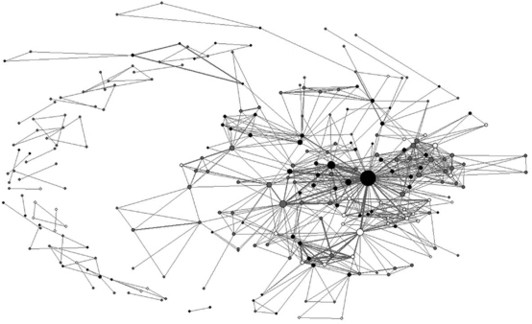

Figure ii illustrates the amalgamation network of all interest groups credited with significant policy enactments since 1945. The nodes are groups partially credited with a policy modify and the links connect actors that were credited with the same policy change. Wider lines connecting two groups indicate that the groups were jointly credited with more policy changes. Black nodes represent liberal organizations. White nodes represent conservative organizations. Grey nodes correspond organizations that could not be categorized ideologically or had a questionable ideological position. The network features i big component and several smaller components, each composed of two to five groups. This indicates that most of the involvement groups credited with enacting policy have indirect ties to many of the other reportedly influential groups. Nearly, but not all, successful attempts to modify policy involve multiple groups; at that place were 55 groups that were credited with a policy change simply not in conjunction with any other groups; they are not pictured. Footnote 14

Network of interest groups credited with policy enactments.The figure depicts an amalgamation network based on involvement groups credited with policy enactments from 1945–2004. Black nodes are liberal organizations; white nodes are bourgeois organizations; others are gray. The links connect groups that were credited with the same enactments (with the width representing the number of shared enactments).

A few important features of the network are visible from the effigy. First, the figure has a core set of interest groups closely connected to one another and a larger periphery of less connected groups. This is consistent with interest group legislative networks (Grossmann and Dominguez, 2009), just less consistent with networks of working relationships among lobbyists (Heinz et al, 1993). 2d, conservative groups are not as common equally liberal groups and are less key in the overall network. This is consistent with the prominence of liberal consequence groups in the advancement customs (Berry, 1999; Grossmann, 2012). Third, there is some ideological clustering, separation between conservative and liberal groups. This is consistent with interest group electoral networks but not with their legislative networks (Grossmann and Dominguez, 2009).

Tabular array four reports some quantitative measures of these features of the network, alongside lists of the well-nigh primal groups in the network. Density is the average number of ties betwixt all pairs of nodes. The depression number signifies that most interest groups are not jointly enacting policy with about others; the average group has a small number of ties. The clustering coefficient measures the extent to which actors create tightly knit groups characterized by loftier density of ties. The clustering coefficient is above one, indicating a moderate degree of clustering. This ways that groups that are connected with one another are also likely to be connected to the aforementioned other groups. The ideological version of the external–internal alphabetize is calculated past subtracting the number of ties inside bourgeois and liberal sets of groups from the number of ties between different ideological groups over the total number of ties. This alphabetize measures the extent to which ties are disproportionately across ideological sectors (positive) or within ideological sectors (negative). The result confirms that in that location is an ideological division between liberal and conservative groups, with ideologically agreeing groups much more probable to be jointly enacting policy together.

The table also includes two measures of the most central actors in the network and the overall centralization of the network. Degree centralization measures the extent to which all ties in the network are to a single role player. Betweeness centralization measures how closely the networks resemble a system in which a small set up of actors appears betwixt all other actors in the network that are not continued to 1 another. Caste centralization is somewhat high and betweeness centralization is quite loftier, indicating that involvement groups in the heart of the network help bridge gaps between other unconnected groups in the network.

The lists of central actors contain substantial overlap. Reported influence on national policy is highly concentrated amidst a small number of well-known interest groups, many of which worked to enact the same policies. The central members are diverse. They include advocacy organizations representing big social groups and large elevation associations. The office of the intergovernmental lobby is also important. Footnote xv Nearly all of the organizations fundamental to this influence network are besides among the most prominent involvement groups in media coverage and the most involved in policy making venues (see Grossmann, 2012). Over the total time catamenia covered past the policy histories, 1945–2004, these groups were amidst the most important in driving policy change. Although there are more unmarried-outcome groups credited with policy change in more than recent years, at that place is a striking consistency to the nearly credited broad actors over the six decades.

Discussion

I find extensive reports of interest grouping influence in federal policy change since 1945 in historical accounts of item policy areas. Interest group influence is reportedly widespread across all branches of government and in almost policy areas. This matches the findings of previous literature reviews (Baumgartner and Leech, 1998; Burstein and Linton, 2002), but is somewhat inconsistent with the literature seeking to tie particular involvement group tactics to policy success (Wawro, 2001; Baumgartner et al, 2009). Policy historians collectively endorse the conventional wisdom that involvement groups influence policy change, rather than some of the counterintuitive findings from quantitative attempts to isolate the role of interest group resource or strategies on policy outcomes.

The most common involvement grouping factor mentioned past historians of policy change was full general back up. This often included idea development, public support and advocacy. Congressional lobbying, generated constituent pressure and inquiry were also somewhat commonly cited tactics. The most frequently credited types of interest groups were advancement organizations, including ideological and single-issue groups as well as identity groups. According to historians of policy change, these groups were partially responsible for more than one-tertiary of all significant mail-war policy changes. Academics and business interests, especially industry trade associations and peak associations, were too judged important.

Surprisingly, involvement group influence does non seem to follow directly from group mobilization. Reported involvement grouping influence on policy change was highest in the Kennedy administration and then declined in the 1970s, just equally the advocacy explosion took off. Policy historians also discover interest group influence where a few groups have large and consequent roles in policy making, rather than when lots of groups mobilize.

Relative interest group influence may besides non follow from resource advantages. Budgetary advantages on one side of a policy consequence, the other key gene that scholars typically investigate as a determinant of interest group influence (see Baumgartner et al, 2009), was almost never mentioned past policy historians as an important determinant of interest grouping influence. PAC contributions too were rarely mentioned. These findings confirm those of a previous meta-analysis of case studies on interest group influence (Burstein and Linton, 2002). Advocacy groups were also seen equally more influential than business interests, professional associations or unions, even though they are less numerous and accept fewer resource. If these historical accounts are to be believed, it suggests that the mechanism for involvement group influence is not probable to be resources exchanges.

These findings may aid to explain the discrepancy betwixt the common claims of interest group influence in example studies of policy making and the difficulty finding consistently influential tactics in the quantitative literature on influence. Scholars typically investigate influence by measuring the corporeality of involvement group action directed toward a specific tactic, such as PAC contributions or lobbying expenditures (see Baumgartner and Leech, 1998). If more groups and more resources exercise non atomic number 82 to more influence, these measures should non exist expected to be consistently associated with influence. Scholars often assume that all interest groups with the aforementioned resources and the same strategies should be every bit likely to be influential. In other words, scholars investigate which groups succeed by comparing resources and strategies. If interest group influence typically results from general support offered by advancement organizations with particular types of reputations, rather than resource advantages or the strategies that groups employ, these methods will non aid us sympathise how some interest groups succeed where others fail.

To the extent that historical analysis of policy alter offers a clear perspective on the mechanisms of interest grouping influence, it points toward the importance of a small number of key groups with reputations for constituency representation. This includes advocacy organizations representing of import public groups, trade associations representing key industries and inter-governmental actors. This is consequent with evidence that interest groups seek to develop reputations for representing stakeholders (Heaney, 2004) and that the few interest groups that develop these reputations are repeatedly involved in policy making (Grossmann, 2012). The findings from the network analysis imply that these prominent involvement groups are highly connected with one another merely that nearly involvement groups lie exterior this subset of central actors.

The Limitations of Learning from Policy History

Policy history offers a worthwhile and contained perspective from that usually found in studies of interest group influence, but that does not mean its findings are definitive. As a source of data on the policy process, several potential biases are likely to be found in policy history. Beginning, like nigh observers of policy, historians may exist less likely to notice policy making in administrative agencies and lower courts compared with laws passed by Congress, executive orders and Supreme Court decisions. 2nd, I have assumed some equality across policy changes of very different scope and importance past reporting frequencies from the population of all meaning policy enactments. Footnote 16 There is an inherent difficulty in comparing across policy changes from dissimilar issue areas and historical periods. In add-on, many policy actions of business organization to some interest groups volition neglect to encounter historians' threshold for reporting on meaning policy developments. The findings reported hither utilise just to pregnant domestic policy changes. Interest group influence on adjustments to particular provisions of policy may non make the cutting, fifty-fifty though they would institute a victory from the perspective of the relevant groups. For instance, policy historians are unlikely to observe business influence on particularized taxation breaks or university success in securing earmarks. Footnote 17

Another important difference between this analysis and previous interest group research is that I only analyze cases of successful policy enactments. Though some authors do present in-depth studies of attempted policy changes that failed, nigh do not. Even when discussing failure to change policy, most authors refer to a general attempt to solve a problem or advance a category of solutions, rather than pointing to a specific neb or regulation that was never enacted. When they do point to a specific proposal that failed, they choose the proposal that came the closest to enactment, making them less helpful comparing cases. The inherent limitation is that the analysis is based on simply enacted policy changes. Close assay of policy change over long periods should provide some expertise in identifying causal factors, but the lack of inclusion of null cases has particular implications for comparing these findings with traditional involvement group research. An analysis of interest group influence on failures to enact policy, for example, would be probable to prove more mutual influence from concern interests. Still failure to enact policy is the easier instance to explain; the status quo bias is widespread in policy making, affecting interest groups and authorities actors (see Baumgartner et al, 2009). Nevertheless, the findings reported here but apply to reported involvement group influence on successful policy enactments.

There are as well some inherent limitations involved in aggregating the explanations of policy historians via the content assay used here. I compile explanations across authors with varying breadth of focus and different standards for adjudicating influence. Some authors cite more than explanatory factors and credit more actors than others. Although I have found few significant differences in the crediting of interest groups based on author bailiwick, upshot focus or research methods, any differences may exist amplified when I compile across authors and when more authors clarify some policy changes compared with others. Although I take institute that these differences practise non explain the results presented here, in that location remains unexplained variation in author judgments. Finally, the network analysis reported here relies on credit given to specific organizations for helping to bring well-nigh policy change. Not all ties in the networks convey political collaboration. The results are thus distinct from past enquiry that analyzes networks of working relationships or coalitions.

Despite these limitations, policy history has several strengths that may help to correct for common problems in interest group enquiry. Offset, information technology does not assume that the same fix of tactics or the same level of resource deployed by different organizations volition be probable to have the same result. It points to the history of working relationships betwixt policymakers and interest groups as well every bit to group reputations and ideas. 2d, policy history regularly compares the policy influence of interest groups with that of diverse other actors throughout government. The lack of interest group influence may simply signal the greater importance of other factors, rather than the failure of interest groups. 3rd, policy history offers the perspective of reviewing policy evolution over an extended period to pick out the most meaning events after policy decisions are taken. I am hopeful that these strengths will non only get-go the limitations of policy history, simply likewise ensure that this assay provides a useful corrective to mutual approaches in involvement group research.

Decision

Accumulation qualitative historical analyses of policy change offers a new picture of interest group influence in the policy making process. Research on federal domestic policy change, since 1945, indicates that involvement group influence is common across venues, fourth dimension periods and event areas. Influence past advocacy groups through full general support and lobbying is the virtually commonly cited factor. Nearly 300 specific interest groups have been credited with post-war policy changes, merely most were infrequently involved. A few prominent groups, such as the AFL-CIO, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Conference of Mayors, have been credited with many different policy enactments and play central roles in the influence network. According to historical accounts, interest group influence was common throughout near of the flow, particularly in the areas of civil rights & liberties, environmental policy, agriculture, and transportation.

These findings should encourage scholars to re-evaluate existing theories of interest group influence and the methods scholars use to judge them. Interest group influence may not follow straight from group or resource mobilization. Our measures of group action may be unlikely to exist associated with influence, fifty-fifty though a few groups regularly influence outcomes. General back up for policy changes by involvement groups recognized equally stakeholders may exist the most important route to influence. Scholars may not be able to clarify the most mutual type of influence without historical studies of how interest groups reach recognized positions in the policy process.

Interest groups likely play an of import role in producing pregnant policy modify. From the perspective of policy historians, involvement group influence is quite common. Yet it may not be institute in the places that involvement grouping scholars usually expect. Assemblage of explanations for policy change in historical narratives is one of import method of assessing when, where, how and why interest group influence occurs. Given that it offers some different answers than traditional interest group scholarship, scholars demand to appraise whether the theories and methods of interest group inquiry allow us to finer assess the frequency or type of interest group influence.

Notes

-

The 14 issue areas cover the entire domestic policy spectrum, every bit defined by the categories used in the Policy Agendas Project. A complete breakdown of issues within each policy area is available at www.policyagendas.org/page/topic-codebook; accessed 24 March 2012.

-

Policy history is a nascent subject field that incorporates political science and history, simply relies mostly on issue area specialists. Most of the authors see themselves as scholars of one consequence surface area, such as environmental policy or education policy, rather than equally historians or political scientists.

-

The focus on meaning policy enactments follows the emphasis of policy historians and scholarly convention (Mayhew, 2005). The findings exercise not extend to less significant policy alter.

-

One notable exception is Michael Heaney's (2006) assay of health policy coalitions.

-

I constitute few significant differences in the extent or type of interest grouping influence based on the type of author or their discipline. University professors represent the vast majority of authors.

-

I compiled published accounts of federal policy alter using bibliographic searches. I searched multiple book catalogs and article databases for every subtopic mentioned in the PAP description of each policy expanse. I then used bibliographies, literature reviews and suggestions from specialists. To locate the 268 sources used here, I reviewed more 800 books and articles. Most of the original sources that I located did non place the most important enactments or review the political process surrounding them. Instead, many focused on advocating policies or explaining the content of policy; these were eliminated. Sources that focused on a single enactment or covered fewer than 10 years of policy making were also excluded. Sources that analyzed the politics of the policy process from a unmarried theoretical orientation without a broad narrative review of policy history were also eliminated. The population for the report is the sources that remained afterward these criteria were practical.

-

The agriculture category, Category 4 in the PAP, covers issues related to farm subsidies and the nutrient supply. The ceremonious rights & liberties policy area, Category 2 from the PAP, includes issues related to discrimination, voting rights, speech communication and privacy. The criminal justice area, Category 12, includes policies related to crime, drugs, weapons, courts and prisons. Educational activity policy, Category 6, includes all levels and types of didactics. The energy result area, Category seven, includes all types of energy production. The surroundings, Category 8, includes air and water pollution, waste management, and conservation. The finance & commerce area, Category 15, includes banking, business regulation and consumer protection. Health policy, Category 3, includes issues related to health insurance, the medical industry and health benefits. Housing & community development, Category xiv, includes housing programs, the mortgage market and aid directed toward cities. Labor & clearing, Category 5, covers employment police force and wages as well every bit immigrant and refugee issues. The macroeconomics area, Category 1, includes all types of tax changes and budget reforms. Science & technology, Category 17, includes policies related to space, media regulation, the calculator manufacture and inquiry. Social welfare, Category 13, includes anti-poverty programs, social services, and aid to the elderly and the disabled. The transportation area, Category 10, includes policies related to highways, airports, railroads and boating.

-

United states of america foreign policy decisionmaking may have unique determinants. It is assessed in a dissever literature inside international relations. The findings reported here do non extend to strange policy.

-

Per cent agreement is the simply acceptable inter-coder reliability measure for many different coders analyzing a single case.

-

Per cent understanding is the simply inter-coder reliability measure out appropriate for compilation of lists from an undefined universe where there is little similarity across cases.

-

I besides adopt several conventions in the display of networks. Degree axis, the number of links for each actor, determines the size of each node. I use spring embedding to determine the layout.

-

Many of these groups did not work lone, even so; they were just credited aslope legislators or administrators, rather than other groups.

-

Land and local governments accept to acquit out the majority of federal policy and, as a consequence, are oftentimes closely involved in policy making (Heclo, 1978).

-

Using a mensurate that differentiates among policy changes based on whether they institute landmark policy changes, small incremental changes or enactments that fall somewhere in between, I have confirmed that the findings reported hither mostly concord across enactments of dissimilar sizes.

-

Although some readers may fright that policy historians would miss more meaning cases of influence by businesses, unions and professional person associations because of differences in the tactics of these groups, I did not find much bear witness for this potential bias. Activities that were out of the public spotlight, such as direct lobbying, were referenced more often than constituent mobilization. Discussions of full general support from interest groups also focused on internal negotiations more frequently than public endorsements and media coverage. Despite this focus, policy historians were simply more likely to credit advancement organizations than other groups. Moreover, they tended to credit broad peak associations with reputations as major representative stakeholders, such as the Chamber of Commerce, the AFL-CIO and the National Association for Manufacturers, even when they did credit business interests or unions. Policy historians may still be collectively wrong to focus on large groups with established reputations, but they did not do so because they focused on public advancement at the expense of lobbying outside the spotlight.

References

-

Baumgartner, F.R. and Leech, B.L. (1998) Basic Interests: The Importance of Groups in Politics and Political Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press.

-

Baumgartner, F.R. and Jones, B.D. (1993) Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago, IL: Academy of Chicago Printing.

-

Baumgartner, F.R., Berry, J.M., Hojnacki, K., Kimball, D.C. and Leech, B.L. (2009) Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

-

Berry, J. (1989) The Involvement Grouping Society, second edn. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

-

Drupe, J. (1999) The New Liberalism: The Rising Power of Citizen Groups. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

-

Burstein, P. and Linton, A. (2002) The affect of political parties, involvement groups, and social motility organizations on public policy: Some recent testify and theoretical concerns. Social Forces 81 (2): 380–408.

-

Davies, G. (2007) Come across Government Abound: Education Politics from Johnson to Reagan. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

-

de Figueiredo, J.M. and Silverman, B.Due south. (2006) Academic earmarks and the returns to lobbying. Journal of Police and Economic science 49 (two): 597–626.

-

Fraser, J.W. (1999) Betwixt Church and State: Organized religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America. New York: St. Martin's Press.

-

Grossmann, 1000. (2012) The Not-So-Special Interests: Interest Groups, Public Representation, and American Governance. Stanford, NY: Stanford University Press.

-

Grossmann, M. and Dominguez, C. (2009) Party coalitions and involvement group networks. American Politics Research 37 (5): 767–800.

-

Hall, R.Fifty. and Wayman, F.W. (1990) Buying time: Moneyed interests and the mobilization of bias in congressional committees. American Political Scientific discipline Review 84 (3): 797–820.

-

Heaney, M.T. (2004) Outside the issue Niche: The multidimensionality of interest group identity. American Politics Research 32 (vi): 611–651.

-

Heaney, 1000.T. (2006) Brokering health policy: Coalitions, parties, and interest group influence. Periodical of Health Politics, Policy and Law 31 (5): 887–944.

-

Heclo, H. (1978) Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment. In: Anthony King (ed.), The New American Political System. Washington DC: American Enterprise Plant, pp. 87–124.

-

Heinz, J.P., Laumann, E.O., Nelson, R.Fifty. and Salisbury, R.H. (1993) The Hollow Core: Private Interests in National Policy Making. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

-

Holyoke, T.T. (2003) Choosing battlegrounds: Interest group lobbying across multiple venues. Political Research Quarterly 56 (3): 325–336.

-

Kingdon, J.West. (2003) Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, second edn. New York: Addison-Wesley.

-

Mahoney, C. (2008) Brussels Versus the Beltway: Advocacy in the United States and the European union. Washington DC: Georgetown University Printing.

-

Mayhew, D.R. (2005) Divided Nosotros Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946–2002. New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Press.

-

Melnick, R.S. (1994) Betwixt the Lines: Interpreting Welfare Rights. Washington DC: The Brookings Establishment.

-

Mitchell, P. (1985) Federal Housing Policy and Programs: Past and Present. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Printing.

-

Patashnik, E. (2003) Afterward the public interest prevails: The political sustainability of policy reform. Governance 16 (2): 203–234.

-

Sabatier, P.A. and Jenkins-Smith, H.C. (1993) Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

-

Schickler, E. (2001) Disjointed Pluralism: Institutional Innovation and the Evolution of the US Congress. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press.

-

Schlozman, Yard.L. and Tierney, J.T. (1986) Organized Interests and American Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

-

Smith, K.A. (2000) American Business organization and Political Power: Public Stance, Elections, and Democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

-

Strickland, Southward.P. (1972) Politics, Science, and Dread Affliction: A Short History of United states of america Medical Research Policy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Printing.

-

Studlar, D.T. (2002) Tobacco Control: Comparative Politics in the U.s. and Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

-

Switzer, J.V. (2003) Disabled Rights: American Inability Policy and the Fight for Equality. Washington DC: Georgetown Academy Press.

-

Walker, J.L. (1991) Mobilizing Interest Groups in America: Patrons, Professions, and Social Movements. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

-

Wawro, Thousand. (2001) A panel probit assay of campaign contributions and roll-call votes. American Journal of Political Science 45 (iii): 563–579.

-

Witko, C. (2006) PACs, issue context, and congressional decisionmaking. Political Research Quarterly 59 (2): 283–295.

Writer data

Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Grossmann, G. Involvement group influence on US policy change: An assessment based on policy history. Int Groups Adv i, 171–192 (2012). https://doi.org/x.1057/iga.2012.ix

-

Published:

-

Upshot Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2012.9

Keywords

- influence

- public policy

- lobbying

- history

- networks

- policy change

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/iga.2012.9

Posted by: sargentthoreeduck.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Most Important Tool For Interest Groups Seeking To Change Or Influence Public Policy?"

Post a Comment